In the near future, might be posting about some systems I am reading about. Let’s start with Twitter Search.

EarlyBird Paper

We start by reading the Early Bird paper.

The paper starts with laying out core design principles. Low-latency and high-throughput are obvious. Ability to present real-time tweets is the unique requirement for Twitter at the time of the paper being written, i.e., new tweets should be immediately searchable. Regarding the second requirement, in the past search engines would crawl the web / index their documents periodically, and the indices were built via batch jobs through technologies such as MapReduce.

Since the time paper was authored (Fall 2011), this has changed. Both Google and Facebook surface real-time results in their search results and feed. But arguably a large fraction of Twitter’s core user intent is real-time content, so they have to get it right.

The core of the paper starts with going over the standard fan-out architecture for distributed systems, with replication & caching for distributing query evaluation and then aggregating results. Then they start to focus specifically on what goes on in a single node while evaluating the query.

For IR newbies: An inverted-index maintains something called ‘posting lists’. Consider them to be something like map<Term, vector<Document>> in C++, i.e., a map from a Term to a list of documents. If I am querying for the term beyonce, I’ll look up the posting list for this term, and the list of documents having that term would be present in the list.

Of course, there can be millions of documents with such a popular term, so there is usually a two-phase querying. In the first phase, we do a cheap evaluation on these documents. This is usually achieved by pre-computing some sort of quality score such as PageRank (which is independent of the query and searcher), keeping the documents in the list sorted in descending order according to this quality score. Then at query time, we get the top $N$ candidates from this vector.

Once we have the candidates, then we do a second phase, which involves a more expensive ranking on these candidates, to return a set of ranked results according to all the signals (query, searcher and document specific features) that we care for.

EarlyBird Overview

EarlyBird is based on Lucene (a Java-based open-source search engine). Each Tweet is assigned a static score on creation, and a resonance score (likes, retweets) which is live-updated. Upon querying, the static score, resonance score and the personalization score, which is computed according to the searcher’s social graph are used to rank the tweets.

At the time of the paper being written, they state the latency between tweet creation and it’s searchability was ~ 10s. Their posting lists store documents in chronological order, and at the time of querying, these documents are queried in reverse chrono order (most recent tweet first).

For querying, they re-use Lucene’s and, or etc. operators. Lucene also supports positional queries (you can ask Lucene to return documents which have term A and B, and both are at-most D distance away from each other in the document).

Index-Organization

EarlyBird seems to handle the problem of concurrent read-writes to the index shard by splitting the shard into ‘segments’. All segments but one are read-only. The mutable index continues to receive writes until it ‘fills up’, at which time it becomes immutable. This is analogous to the ‘memtable’ architecture of LSM trees. But I wonder if they do any sort of compactions on the segments. This is not clearly explained here.

Layout for Mutable (Unoptimzed) Index: Then they discuss the problem of how to add new tweets into posting lists. Their posting lists at the time, were supposed to return reverse-chrono results. So they don’t use any sort of document score to sort the results. Instead tweet timestamp is what they want for ordering.

Appending at the end of posting lists, doesn’t gel well with delta-encoding schemes, since they naturally work with forward traversal, and they would have to traverse backwards. Pre-pending at the beginning of the lists using naive methods such as linked lists would be unfriendly for the cache, and require additional memory footprint for the next pointers.

They fall-back to using arrays. The posting list is an array, with 32-bit integer values, where they reserve 24 bits for the document id, and 8 bits for the position of the term in the document. 24 bits is sufficient, because firstly they map global tweet ids, to a local document id in that posting list, secondly their upper limit of how many tweets can go in a segment is < $2^{23}$. Though, I might want to keep additional meta-data about a document, and not just position of the term, so this is a little too-specific for tweets at the time of the paper being authored.

They also keep pools of pre-allocated arrays, or slices (of sizes $2^1$, $2^4$, $2^7$ and $2^{11}$), similar to how a Buddy allocator works. When a posting list exhausts it’s allocated array (slice), they allocate another one which is 8x bigger, until you reach a size of $2^{11}$. There is some cleverness in linking together these slices. If you can get this linking to work, you would not have to do $O(N)$ copy of your data as you outgrow your current allocated slice.

Layout for Immutable (Optimized) Index: The approach of pools is obviously not always efficient. We can end up wasting ~ 50% of the space, if the number of documents for a term are pathologically chosen. In the optimized index, the authors have a concept of long and short posting lists. Short lists are the same as in the unoptimized index.

The long lists comprise of blocks of 256 bytes each. The first four bytes have the first posting uncompressed. The remaining bytes are used to store the document id delta from the previous entry, and the position of the term in a compressed form. I wonder why they don’t do this compression to the entire list, and why have compressed blocks? My guess is that compressing the entire list would be prohibit random access.

Concurrency:

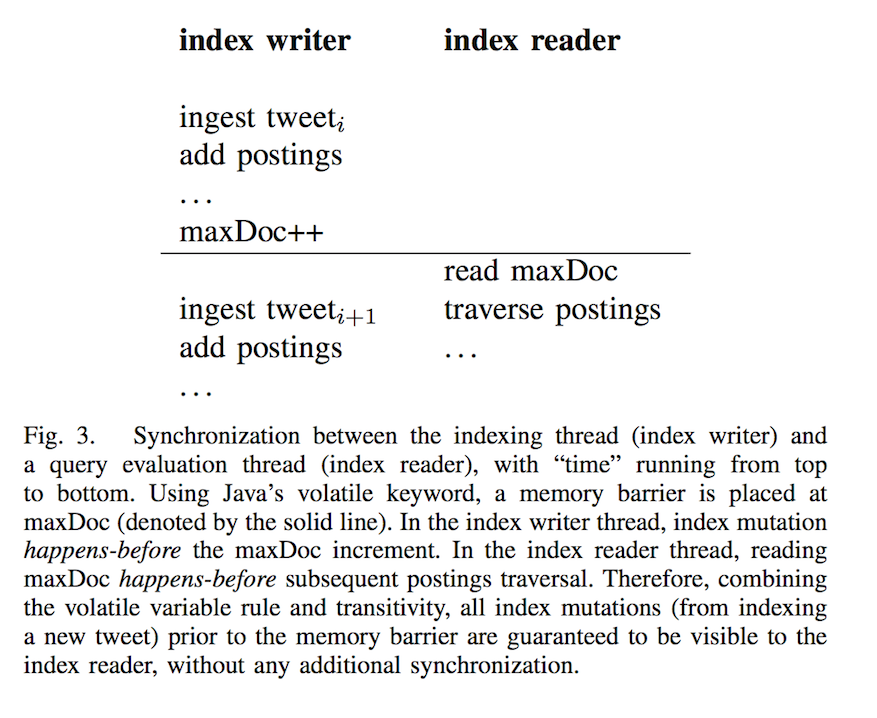

Most of the heavy-lifting of consistency within a specific posting list reader-writers is done by keeping a per-posting list value of the maximum document id encountered so far (maxDoc). Keeping this value as volatile in Java introduces a memory barrier. So that there is consistency without giving up too much performance.

Overall

The paper was very easy to read. I would have hoped that the authors would have described how the switching between immutable-to-mutable index happens, how is the index persisted to disk, etc., apart from addressing the rigid structure of meta-data in each posting list entry (just the term position).

Omnisearch and Improvements on EarlyBird

There are a couple of new posts about improvements on top of EarlyBird.

Introducing Omnisearch

This blogpost introduces Omnisearch. As I mentioned earlier, EarlyBird is strongly tied to the tweet’s content. In mature search systems, there are several “verticals”, which the infra needs to support. This blogpost describes how they are moving to a generic infrastructure which can be used to index media, tweets, users, moments, periscopes, etc.

Omnisearch Index Formats

Here is the blogpost, on this topic. It goes over what is mentioned in the paper before describing their contributions. They mostly work on the optimized index, as described earlier.

If a document has duplicate terms, it occurs that many times in the old posting list format. In the new format, they keep (document, count) pairs, instead of (document, position) pairs. They keep another table for positions. To further optimize, since most counts are 1, they store (document, count-1) pairs. They achieve a 2% space saving and 3% latency drop. I’m not entirely convinced why this improves both for tweet-text only index.

However, for indexing terms which are not present in the text (such as for user indices, where we want to keep a term for verified users) and hence the position does not make any sense. In that case, a separate position table makes sense, because we can completely skip the table in those cases.

Super-Root

Super-Root is another layer on top of Twitter’s index servers, which exposes a single API to customers, instead of having them query individual indices themselves.

Super-Root allows them to abstract away lower-level changes, add features like quota limitations, allow query optimization, and allow having thin clients. This is pretty essential when you start having a large number of customers.