Recurrent Neural Networks are pretty interesting. Please read Andrej Karpathy’s post about their effectiveness here, if you haven’t already. I am not going to cover a lot of new material in the post, but mostly drawing inspiration from his min-char-rnn and R2RT’s post about RNNs, and giving a gentle intro to using TF to write a simple RNN.

I picked TensorFlow rather than Caffe, because of the possibility of being able to run my code on mobile, which I enjoy. Also, the documentation and community around TF seemed slightly more vibrant than Caffe/Caffe2.

What we want to do is:

- Feed the RNN some input text, one character at a time.

- Train the RNN to predict the next character.

- The RNN keeps a hidden state (some sort of context), it should be able to learn to predict the next character accurately.

- Try to do it without using the fancy stuff as much as possible.

Quick Intro

The hidden state at time step $t$ is $h_t$ is a function of the hidden step at the previous time-step, and the current input. Which is:

- $h_t = f_W(h_{t-1}, x_t)$

$f_W$ can be expanded to:

- $h_t = \tanh(W_{xh}x_{t} + W_{hh}h_{t-1})$

$W_{xh}$ is a matrix of weights for the input at that time $x_t$. $W_{hh}$ is a matrix of weights for the hidden-state at the previous time-step, $h_{t-1}$.

Finally, $y_{t}$, the output at time-step $t$ is computed as:

- $y_{t} = W_{hy}h_{t}$

Dimensions:

For those like me who are finicky about dimensions:

- Assuming input $x_t$ is of size $V \times N$. Where $V$ is the size of one example, and there are $N$ examples.

- Our hidden state per example is of size $H$, so $h_i$ is of size $H \times N$ for all $N$ examples.

- Easy to infer then is $W_{xh}$ is of size $H \times V$, $W_{hh}$ is of size $H \times H$.

- $y_t$ has to be of size $V \times N$, hence $W_{hy}$ is of size $V \times H$

Code Walkthrough

This is my implementation of min-char-rnn, which I am going to use for the purpose of the post.

We start with just reading the input data, finding the distinct characters in the vocabulary, and associating an integer value with each character. Pretty standard stuff.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

Then we specify our hyperparameters, such as size of the hidden state ($H$). seq_length is the number of steps we will train an RNN per initialization of the hidden state. In other words, this is the maximum context the RNN is expected to retain while training.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

We have a method called genEpochData which does nothing fancy, apart from breaking the data into batch_size number of batches, each with a fixed number of examples, where each example has an (x, y) pair, both of which are of seq_length length. x is the input, and y is the output.

In our current setup, we are training the network to predict the next character. So y would be nothing but x shifted right by one character.

Now that we have got the boiler-plate out of the way, comes the fun part.

Light-Weight Intro to TensorFlow

The way TensorFlow (TF) works is that it creates a computational graph. With numpy, I was used to creating variables which hold actual values. So data and computation went hand-in-hand.

In TF, you define ‘placeholders’, which are where your input will go, such as place holders for x and y, like so:

1 2 3 | |

Then you can define ‘operations’ on these input placeholders. In the code below, we convert x and y to their respective ‘one hot’ representations (a binary vector of size, vocab_size, where the if the value of x is i, the i-th bit is set).

1 2 3 | |

This is a very simple computation graph, wherein if we set the placeholders correctly, x_oh and y_oh will have the corresponding one-hot representations of the x and y. But you can’t print out their values directly, because they don’t contain them. We need to evaluate them through a TF session (coming up later in the post).

One can also define variables, such as when defining the hidden state, we do it this way:

1

| |

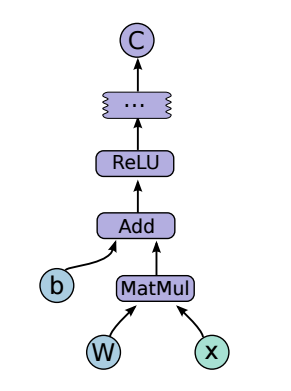

We’ll use the above declared variable and placeholders to compute the next hidden state, and you can compute arbitrarily complex functions this way. For example, the picture below from the TF whitepaper shows how can we represent the output of a Feedforward NN using TF (b and W are variables, and x is the placeholder. Everything else is an operation).

Simple RNN using TF

The code below computes $y_t$, given the $x_t$ and $h_{t-1}$.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Now we are ready to complete our computation graph.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

As we saw above, we can compute the total loss in the batch pretty easily. This is usually the easier part.

While doing CS231N assignments, I learned the harder part was the back-prop, which is based on how off your predictions are from the expected output.You need to compute the gradients at each stage of the computation graph. With large computation graphs, this is tedious and error prone. What a relief it is, that TF does it for you automagically (although it is super to know how backprop really works).

1 2 | |

Evaluating the graph

Evaluating the graph is pretty simple too. You need to initialize a session, and then initialize all the variables. The run method of the Session object does the execution of the graph. The first input is the list of the graph nodes that you want to evaluate. The second argument is the dictionary of all the placeholders.

It returns you the list of values for each of the requested nodes in order.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

After this, it is pretty easy to stitch all this together into a proper RNN.

Results

While writing the post, I discovered a couple of implementation issues, which I plan to fix. But nevertheless, training on a Shakespeare’s ‘The Tempest’, after a few hundred epochs, the RNN generated this somewhat english-like sample:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Not too bad. It learns that there are characters named Sebastian and Ferdinand. And mind you this was a character level model, so this isn’t super crappy :-)

(All training was done on my MBP. No NVidia GPUs were used whatsoever. I have a good ATI Radeon GPU at home, but TF doesn’t support OpenCL yet. It’s coming soon-ish though.)