Taking inspiration from Werner Vogel’s ‘Back to Basics’ blogposts, here is one of my own posts about fundamental topics. While on a long-haul flight with no internet connectivity, having exhausted the books on my kindle, and hardly any inflight-entertainment, I decided to code up Linear Regression in Python. Let’s look at both the theory and implementation of the same.

Theory

Essentially, in Linear Regression, we try to estimate a dependent variable $y$, using independent variables $x_1$, $x_2$, $x_3$, $…$, using a linear model.

More formally, $y = b + W_1 x_1 + W_2 x_2 + … + W_n x_n + \epsilon$. Where, $W$ is the weight vector, $b$ is the bias term, and $\epsilon$ is the noise in the data.

It can be used when there is a linear relationship between the input $X$ (input vector containing all the $x_i$, and $y$).

One example could be, given a vending machine’s sales of different kind of soda, predict the total profit made. Let’s say there are three kinds of soda, and for each can of that variety sold, the profit is 0.25, 0.15 and 0.20 respectively. Also, we know that there will be a fixed cost in terms of electricity and maintenance for the machine, this will be our bias, and it will be negative. Let’s say it is $100. Hence, our profit will be:

$y = -100 + 0.25x_1 + 0.15x_2 + 0.20x_3$.

The problem is usually the inverse of the above example. Given the profits made by the vending machine, and sales of different kinds of soda (i.e., several pairs of $(X_i, y_i)$), find the above equation. Which would mean being able to find $b$, and $W$. There is a closed-form solution for Linear Regression, but it is expensive to compute, especially when the number of variables is large (10s of thousands).

Generally in Machine Learning the following approach is taken for similar problems:

- Make a guess for the parameters ($b$ and $W$ in our case).

- Compute some sort of a loss function. Which tells you how far you are from the ideal state.

- Find how much you should tweak your parameters to reduce your loss.

Step 1 The first step is fairly easy, we just pick a random $W$ and $b$. Let’s say $\theta = (W, b)$, then $h_\theta(X_i) = b + X_i.W$. Given an $X_i$, our prediction would be $h_\theta(X_i)$.

Step 2 For the second step, one loss function could be, the average absolute difference between the prediction and the real output. This is called the ‘L1 norm’.

$L_1 = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} \text{abs}(h_\theta(X_i) - y_i)$

L1 norm is pretty good, but for our case, we will use the average of the squared difference between the prediction and the real output. This is called the ‘L2 norm’, and is usually preferred over L1.

$L_2 = \frac{1}{2n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} (h_\theta(X_i) - y_i)^2$.

Step 3 We have two sets of params $b$ and $W$. Ideally, we want $L_2$ to be 0. But that would depend on the choices of these params. Initially the params are randomly chosen, but we need to tweak them so that we can minimize $L_2$.

For this, we follow the Stochastic Gradient Descent algorithm. We will compute ‘partial derivatives’ / gradient of $L_2$ with respect to each of the parameters. This will tell us the slope of the function, and using this gradient, we can adjust these params to reduce the value of the method.

Again,

$L_2 = \frac{1}{2n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} (h_\theta(X_i) - y_i)^2$.

Deriving w.r.t. $b$ and applying chain rule,

$\large \frac{\partial L}{\partial b}$ = $2 . \large\frac{1}{2n}$ $\sum_{i=1}^{n} (h_\theta(X_i) - y_i) . 1$ (Since, $\frac{\partial (h_\theta(X_i) - y_i)}{\partial b} = 1$)

$ \implies \large \frac{\partial L}{\partial b}$ $= \sum_{i=1}^{n} (h_\theta(X_i) - y_i)$

Similarly, deriving w.r.t. $W_j$ and applying chain rule,

$\large \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_j}$ = $\large\frac{1}{n}$ $\sum_{i=1}^{n} (h_\theta(X_i) - y_i) . X_{ij}$

Hence, at each iteration, the updates we will perform will be,

$b = b - \eta \large\frac{\partial L}{\partial b}$, and, $W_j = W_j - \eta \large\frac{\partial L}{\partial W_j}$.

Where, $\eta$ is what is called the ‘learning rate’, which dictates how big of an update we will make. If we choose this to be to be small, we would make very small updates. If we set it to be a large value, then we might skip over the local minima. There are a lot of variants of SGD with different tweaks around how we make the above updates.

Eventually we should converge to a value of $L_2$, where the gradients will be nearly 0.

Implementation

The complete implementation with dummy data in about 100 lines is here. A short walkthrough is below.

The only two libraries that we use are numpy (for vector operations) and matplotlib (for plotting losses). We generate random data without any noise.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Where num_rows is $n$ as used in the above notation, and num_feats is the number of variables. We define the class LinearRegression, where we initialize W and b randomly initially. Also, the predict method computes $h_\theta(X)$.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

The crux of the code is in the train method, where we compute the gradients.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 | |

For the given input, with the fixed seed and five input variables, the solution as per the code is:

1 2 | |

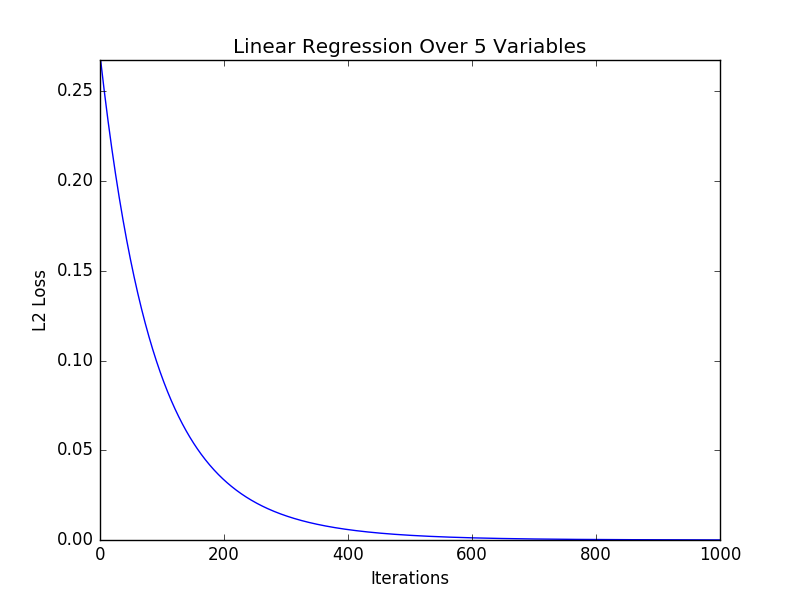

This is how the $L_2$ loss converges over number of iterations:

To verify that this is actually correct, I serialized the input to a CSV file and used R to solve this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

The intercept is same as $b$, and the rest five outputs are the $W_i$, and are similar to what my code found.